Stéphane Degout (King); Barbara Hannigan (Isabel); Gyula Orendt (Gaveston/Stranger); Peter Hoare (Mortimer); Samuel Boden (Boy/Young King); Jennifer France (Witness 1/Singer 1/Woman 1); Krisztina Szabó (Witness 2/Singer 2/Woman 2); Andri Björn Róbertsson (Witness 3/Madman)

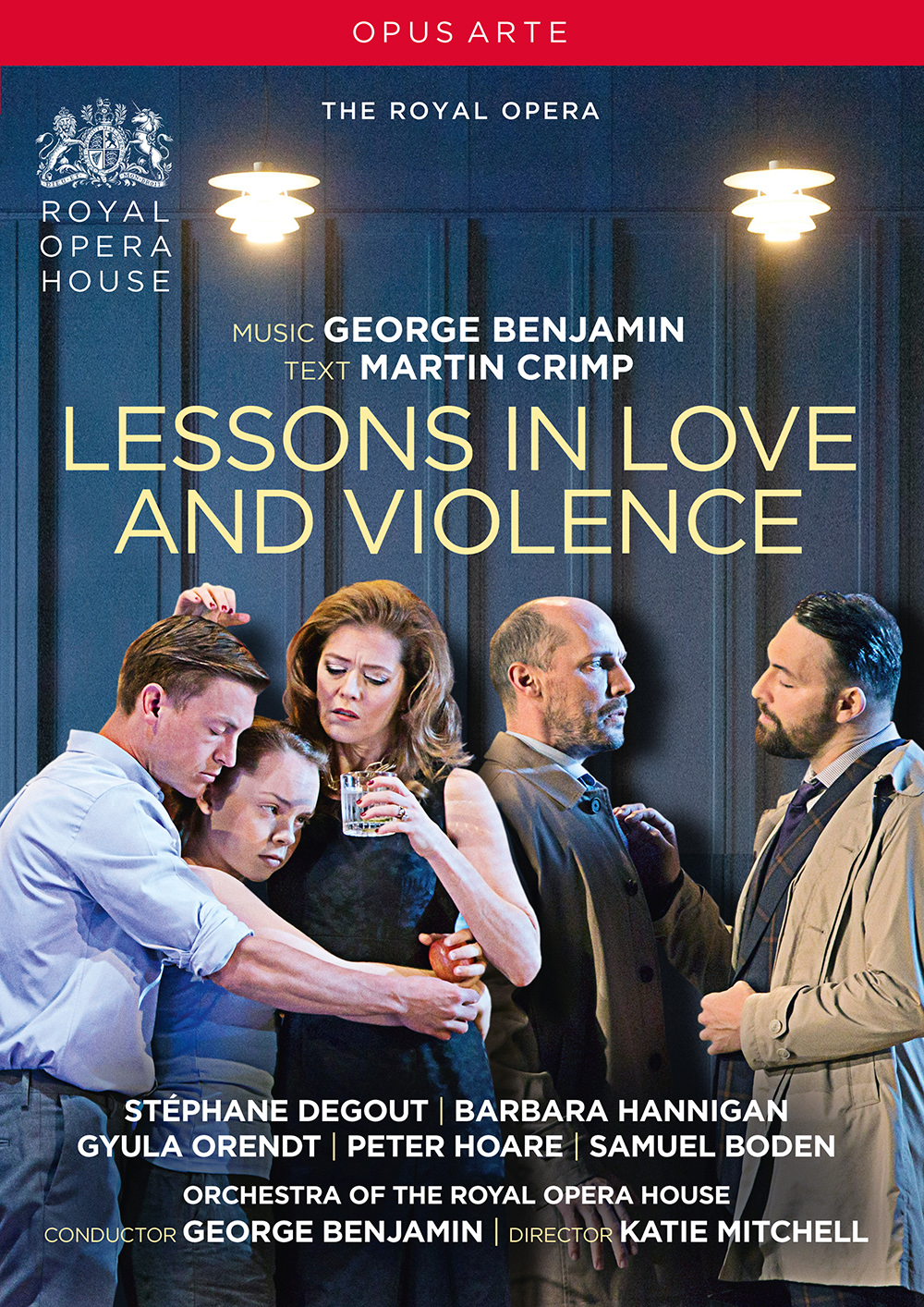

George Benjamin and Martin Crimp’s second full-length opera – following the acclaimed Written on Skin – draws on the real-life relationship between Edward II and Piers Gaveston to explore how personal relationships can have fatal political consequences. The King lives in a close but uneasy relationship with his wife Isabel, their two children and his lover Gaveston. When the King banishes his military advisor Mortimer, he sets off a chain of devastating events.

Benjamin’s richly-orchestrated score perfectly captures the drama’s intense emotions, while director Katie Mitchell provides a visually stunning contemporary staging, highlighting the timelessness of the opera’s main themes. The composer himself conducts a superb international cast.

DVD

BLU-RAY

George Benjamin

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

Stéphane Degout; Barbara Hannigan; Gyula Orendt; Peter Hoare; Samuel Boden; Jennifer France; Krisztina Szabó; Andri Björn Róbertsson; Orchestra of the Royal Opera House; George Benjamin

Hannigan is outstanding, as ever, as Isabel. Stéphane Degout and Gyula Orendt are well matched as the King and Gaveston/Stranger, the latter swathed in a mystic accompaniment of gentle percussion. Peter Hoare brings a fearsome authority to Mortimer and Samuel Boden is inspired casting as the Boy, growing up to be King.

Lessons in Love and Violence is not an opera that is going to inspire affection. What it does have is the most gripping concentration, enough to make an audience hold its breath for long stretches at a time. In Katie Mitchell’s razor-sharp production, the opera is set in a high-end, modern development, where the walls are hung with paintings in the style of Francis Bacon. Is she telling us that the horrors we witness are, in fact, a prediction for our own time? It is a depressing thought." (The Financial Times ★★★★)

"Although Marlowe’s play was in Crimp’s mind when he began to create his operatic text, the result is an independent drama that Mortimer’s smart and fluent designs, based around an adaptable unit set, place visually in the here-and-now.

While there’s no disguising that the central character is the English monarch forced to abdicate and then murdered in 1327, he is referred to only as the King (a finely detailed performance from Stephane Degout), while his son and successor Edward III is initially the Boy and later the Young King (sympathetically realised by Samuel Boden). Most of the other historical figures – Edward’s wife Isabel (sung with immaculate focus by Barbara Hannigan), his disloyal, authoritarian henchman Mortimer (convincingly repellent in Peter Hoare’s interpretation), and his lover Gaveston (a subtly ambivalent portrayal from Gyula Orendt), retain theirs. Meanwhile, in a silent, unnamed part as Edward’s daughter – referred to as Young Girl – Ocean Barrington-Cook retains a watchful and increasingly compelling presence.

The focus of Crimp’s resonant libretto is the collision between love and power, articulated in Mortimer’s anger at Edward’s relationship with Gaveston, which causes him to set in motion the king’s removal; in Katie Mitchell’s disciplined staging not only do we see Edward and Gaveston destroyed, but also how Edward’s children in turn learn lessons in violence.

Crimp knows how to leave room for music to amplify his points – which Benjamin’s fascinating score does with boundless technical skill and unceasing eloquence. The composer conducts an outstanding performance." (The Stage ★★★★★)

"There can’t be much doubt about it: whatever one’s personal quibbles or the collective scepticism of a minority of nay-sayers, this new opera by composer George Benjamin and playwright Martin Crimp looks set to prove another international success on the level of their previous collaborations, Into the Little Hill and Written on Skin.

Lessons in Love and Violence intrigues and compels. Charged with music of exquisite beauty and a potent narrative, it is immaculately staged and performed. The artistry involved is consummate.

But Crimp has certainly fulfilled the librettist’s primary task of inspiring the composer. The vocabulary employed is very simple, predominantly monosyllabic, and one can understand why Benjamin relished setting such words to music. Bar a few flights into extreme soprano territory, the vocal lines are often gently conversational. Compared to Written in Skin, there are more overtly lyrical passages (especially in the erotic duets for the King and Gaveston), more vocal counterpoint (including some almost Verdian ensembles) and more bravura orchestral writing (in the interludes between the scenes). The pacing and balance are flawless. The influence of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande is ubiquitous, and the ghost of Britten materialises at places too.

Benjamin’s great gift for crystalline clarity is also evident: I can’t think of a composer writing today who has the same ability to make the tiniest flourish or the simplest combination of instruments so richly expressive. There is no empty rhetoric in his music, no pointless excess, and yet it never seems to splutter: the flow is unimpeded.

Katie Mitchell has provided a cool, clean and meticulously choreographed staging that ignores the tale’s medieval roots and gives little indication of the changes of scene. Designed by Vicki Mortimer, its modern setting short-changes the elements of absolutist power and courtly rank that the text emphasises and leaves it slightly bloodless: Mitchell’s approach mesmerises, but I can imagine another less bleak interpretation.

For the cast, I have nothing but praise: two superb baritones, Stéphane Degout and Gyula Orendt, are ideal as the King and Gaveston. Peter Hoare is in clarion voice as the two-timing Mortimer, Sam Boden makes his mark as the boy king with a nasty surprise up his royal sleeve. As Isabel, the phenomenal Barbara Hannigan does what she always does, but does it brilliantly. A special word too for Oceana Barrington-Cook, very touching as the boy’s mute sister. Benjamin conducts with a composer’s authority, nobly honoured by the orchestra." (The Daily Telegraph ★★★★)

"One can only admire the valiant ensemble performance, with Stéphane Degout’s king, Hannigan’s compelling queen, tenor Peter Hoare’s trenchant royal adviser Mortimer, and fellow tenor Samuel Boden’s pure-toned royal successor all making the most of their very demanding parts.

Meanwhile Benjamin’s fabled brilliance as an orchestrator produces a finely wrought sonic tapestry: it’s as accessible as film music, but with original effects thanks to compositional alchemy and unfamiliar instruments including a cimbalom and steel drums. The vocal line may be relentless recitative, but the instrumental sound world is a seductive amalgam of late romanticism and early modernism. The interludes with which the scenes are punctuated could be extracted to form the basis for a lovely orchestral suite." (Evening Standard)

"George Benjamin and Martin Crimp have done it again.

Six years after their previous operatic collaboration, the masterly “Written on Skin,” Mr. Benjamin and Mr. Crimp have again dared to challenge audiences by remaining true to their uncompromising visions. In “Lessons in Love and Violence,” which opened here on Thursday at the Royal Opera House, the music, written and compellingly conducted by Mr. Benjamin, is unapologetically modernist, while the libretto, by Mr. Crimp, is often cryptic. Without pandering, they’ve made another significant contribution to the art form.

In the queen, Mr. Benjamin has created another remarkable role for Ms. Hannigan’s immense vocal gifts and comprehensive musicianship. He writes lines that shift from earthy emotionalism to angelic purity, knowing that this artist can handle those pivots. He takes advantage of her focused intonation and rhythmic precision to lend even anguished passages structural strength.

But it’s Mr. Benjamin’s remarkable music that gives the work its charge: The writing is so lush, haunting and detailed — radiant one moment, piercingly dissonant the next — that you are continuously enveloped by the raucous beauty of the sounds.

As the opening scene begins, needling brass riffs protrude over sputtering clusters of hard-edged chords. Sometimes a bed of strings will swell with a prolonged sonority, though the component notes are too restless to stay put. Instrumental lines emerge from atmospheric murmurs, trying to coalesce into melodic fragments.

Mr. Crimp’s text, as in “Written on Skin,” is enigmatic. “You know where I am: inside your life,” Gaveston tells the King. Early on, the King warns Mortimer, who is clearly drawn to the queen, that wherever Mortimer touches the “immaculate surface” of Isabel’s skin, “your politics will leave streaks of my blood.”

Mr. Benjamin savors the strangeness of these words. He was determined, he says in an interview in the program book, to set the text so that it would be audible. He does so impressively, aided by the crisp diction of the singers, often by following the natural rhythms of speech. But he knows when to allow a vocal line to turn mellifluous." (New York Times)

"In the libretto Edward is known simply as the King; his wife Isabella becomes Isabel, Gaveston retains his name and Mortimer is the military advisor who precipitates the crisis in the monarch’s private and public lives. The text is spare, its language more or less timeless, and fits easily into the 21st-century setting of Mitchell’s beautifully detailed production. The set is an elegant bedroom, viewed from different sides in each scene; on one wall is a Francis Bacon-like portrait, and on another a fully stocked and beautifully lit marine aquarium, which is seen emptied and devoid of all life in the opera’s second half.

There’s a pervading air of menace, but the drama’s implicit violence only becomes explicit in some of the orchestral interludes. If Benjamin’s score is not quite as luminous and beguiling as his orchestral writing in Written in Skin, there are still some remarkable colours and effects – soaring horn lines, long, self-renewing melodic strands, pungent punctuations from cimbalom and wooden percussion. That is matched in some of Benjamin’s vocal writing, especially Isabel’s spiralling melismas , tailor-made for Barbara Hannigan’s extraordinary agility, and the lustrous honeyed lines in the final scenes for the the high-tenor role of the Son (who becomes Edward III), beautifully delivered by Samuel Boden." (The Guardian ★★★★)

Stéphane Degout (King); Barbara Hannigan (Isabel); Gyula Orendt (Gaveston/Stranger); Peter Hoare (Mortimer); Samuel Boden (Boy/Young King); Jennifer France (Witness 1/Singer 1/Woman 1); Krisztina Szabó (Witness 2/Singer 2/Woman 2); Andri Björn Róbertsson (Witness 3/Madman)

George Benjamin and Martin Crimp’s second full-length opera – following the acclaimed Written on Skin – draws on the real-life relationship between Edward II and Piers Gaveston to explore how personal relationships can have fatal political consequences. The King lives in a close but uneasy relationship with his wife Isabel, their two children and his lover Gaveston. When the King banishes his military advisor Mortimer, he sets off a chain of devastating events.

Benjamin’s richly-orchestrated score perfectly captures the drama’s intense emotions, while director Katie Mitchell provides a visually stunning contemporary staging, highlighting the timelessness of the opera’s main themes. The composer himself conducts a superb international cast.

DVD

BLU-RAY

George Benjamin

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

Stéphane Degout; Barbara Hannigan; Gyula Orendt; Peter Hoare; Samuel Boden; Jennifer France; Krisztina Szabó; Andri Björn Róbertsson; Orchestra of the Royal Opera House; George Benjamin

Hannigan is outstanding, as ever, as Isabel. Stéphane Degout and Gyula Orendt are well matched as the King and Gaveston/Stranger, the latter swathed in a mystic accompaniment of gentle percussion. Peter Hoare brings a fearsome authority to Mortimer and Samuel Boden is inspired casting as the Boy, growing up to be King.

Lessons in Love and Violence is not an opera that is going to inspire affection. What it does have is the most gripping concentration, enough to make an audience hold its breath for long stretches at a time. In Katie Mitchell’s razor-sharp production, the opera is set in a high-end, modern development, where the walls are hung with paintings in the style of Francis Bacon. Is she telling us that the horrors we witness are, in fact, a prediction for our own time? It is a depressing thought." (The Financial Times ★★★★)

"Although Marlowe’s play was in Crimp’s mind when he began to create his operatic text, the result is an independent drama that Mortimer’s smart and fluent designs, based around an adaptable unit set, place visually in the here-and-now.

While there’s no disguising that the central character is the English monarch forced to abdicate and then murdered in 1327, he is referred to only as the King (a finely detailed performance from Stephane Degout), while his son and successor Edward III is initially the Boy and later the Young King (sympathetically realised by Samuel Boden). Most of the other historical figures – Edward’s wife Isabel (sung with immaculate focus by Barbara Hannigan), his disloyal, authoritarian henchman Mortimer (convincingly repellent in Peter Hoare’s interpretation), and his lover Gaveston (a subtly ambivalent portrayal from Gyula Orendt), retain theirs. Meanwhile, in a silent, unnamed part as Edward’s daughter – referred to as Young Girl – Ocean Barrington-Cook retains a watchful and increasingly compelling presence.

The focus of Crimp’s resonant libretto is the collision between love and power, articulated in Mortimer’s anger at Edward’s relationship with Gaveston, which causes him to set in motion the king’s removal; in Katie Mitchell’s disciplined staging not only do we see Edward and Gaveston destroyed, but also how Edward’s children in turn learn lessons in violence.

Crimp knows how to leave room for music to amplify his points – which Benjamin’s fascinating score does with boundless technical skill and unceasing eloquence. The composer conducts an outstanding performance." (The Stage ★★★★★)

"There can’t be much doubt about it: whatever one’s personal quibbles or the collective scepticism of a minority of nay-sayers, this new opera by composer George Benjamin and playwright Martin Crimp looks set to prove another international success on the level of their previous collaborations, Into the Little Hill and Written on Skin.

Lessons in Love and Violence intrigues and compels. Charged with music of exquisite beauty and a potent narrative, it is immaculately staged and performed. The artistry involved is consummate.

But Crimp has certainly fulfilled the librettist’s primary task of inspiring the composer. The vocabulary employed is very simple, predominantly monosyllabic, and one can understand why Benjamin relished setting such words to music. Bar a few flights into extreme soprano territory, the vocal lines are often gently conversational. Compared to Written in Skin, there are more overtly lyrical passages (especially in the erotic duets for the King and Gaveston), more vocal counterpoint (including some almost Verdian ensembles) and more bravura orchestral writing (in the interludes between the scenes). The pacing and balance are flawless. The influence of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande is ubiquitous, and the ghost of Britten materialises at places too.

Benjamin’s great gift for crystalline clarity is also evident: I can’t think of a composer writing today who has the same ability to make the tiniest flourish or the simplest combination of instruments so richly expressive. There is no empty rhetoric in his music, no pointless excess, and yet it never seems to splutter: the flow is unimpeded.

Katie Mitchell has provided a cool, clean and meticulously choreographed staging that ignores the tale’s medieval roots and gives little indication of the changes of scene. Designed by Vicki Mortimer, its modern setting short-changes the elements of absolutist power and courtly rank that the text emphasises and leaves it slightly bloodless: Mitchell’s approach mesmerises, but I can imagine another less bleak interpretation.

For the cast, I have nothing but praise: two superb baritones, Stéphane Degout and Gyula Orendt, are ideal as the King and Gaveston. Peter Hoare is in clarion voice as the two-timing Mortimer, Sam Boden makes his mark as the boy king with a nasty surprise up his royal sleeve. As Isabel, the phenomenal Barbara Hannigan does what she always does, but does it brilliantly. A special word too for Oceana Barrington-Cook, very touching as the boy’s mute sister. Benjamin conducts with a composer’s authority, nobly honoured by the orchestra." (The Daily Telegraph ★★★★)

"One can only admire the valiant ensemble performance, with Stéphane Degout’s king, Hannigan’s compelling queen, tenor Peter Hoare’s trenchant royal adviser Mortimer, and fellow tenor Samuel Boden’s pure-toned royal successor all making the most of their very demanding parts.

Meanwhile Benjamin’s fabled brilliance as an orchestrator produces a finely wrought sonic tapestry: it’s as accessible as film music, but with original effects thanks to compositional alchemy and unfamiliar instruments including a cimbalom and steel drums. The vocal line may be relentless recitative, but the instrumental sound world is a seductive amalgam of late romanticism and early modernism. The interludes with which the scenes are punctuated could be extracted to form the basis for a lovely orchestral suite." (Evening Standard)

"George Benjamin and Martin Crimp have done it again.

Six years after their previous operatic collaboration, the masterly “Written on Skin,” Mr. Benjamin and Mr. Crimp have again dared to challenge audiences by remaining true to their uncompromising visions. In “Lessons in Love and Violence,” which opened here on Thursday at the Royal Opera House, the music, written and compellingly conducted by Mr. Benjamin, is unapologetically modernist, while the libretto, by Mr. Crimp, is often cryptic. Without pandering, they’ve made another significant contribution to the art form.

In the queen, Mr. Benjamin has created another remarkable role for Ms. Hannigan’s immense vocal gifts and comprehensive musicianship. He writes lines that shift from earthy emotionalism to angelic purity, knowing that this artist can handle those pivots. He takes advantage of her focused intonation and rhythmic precision to lend even anguished passages structural strength.

But it’s Mr. Benjamin’s remarkable music that gives the work its charge: The writing is so lush, haunting and detailed — radiant one moment, piercingly dissonant the next — that you are continuously enveloped by the raucous beauty of the sounds.

As the opening scene begins, needling brass riffs protrude over sputtering clusters of hard-edged chords. Sometimes a bed of strings will swell with a prolonged sonority, though the component notes are too restless to stay put. Instrumental lines emerge from atmospheric murmurs, trying to coalesce into melodic fragments.

Mr. Crimp’s text, as in “Written on Skin,” is enigmatic. “You know where I am: inside your life,” Gaveston tells the King. Early on, the King warns Mortimer, who is clearly drawn to the queen, that wherever Mortimer touches the “immaculate surface” of Isabel’s skin, “your politics will leave streaks of my blood.”

Mr. Benjamin savors the strangeness of these words. He was determined, he says in an interview in the program book, to set the text so that it would be audible. He does so impressively, aided by the crisp diction of the singers, often by following the natural rhythms of speech. But he knows when to allow a vocal line to turn mellifluous." (New York Times)

"In the libretto Edward is known simply as the King; his wife Isabella becomes Isabel, Gaveston retains his name and Mortimer is the military advisor who precipitates the crisis in the monarch’s private and public lives. The text is spare, its language more or less timeless, and fits easily into the 21st-century setting of Mitchell’s beautifully detailed production. The set is an elegant bedroom, viewed from different sides in each scene; on one wall is a Francis Bacon-like portrait, and on another a fully stocked and beautifully lit marine aquarium, which is seen emptied and devoid of all life in the opera’s second half.

There’s a pervading air of menace, but the drama’s implicit violence only becomes explicit in some of the orchestral interludes. If Benjamin’s score is not quite as luminous and beguiling as his orchestral writing in Written in Skin, there are still some remarkable colours and effects – soaring horn lines, long, self-renewing melodic strands, pungent punctuations from cimbalom and wooden percussion. That is matched in some of Benjamin’s vocal writing, especially Isabel’s spiralling melismas , tailor-made for Barbara Hannigan’s extraordinary agility, and the lustrous honeyed lines in the final scenes for the the high-tenor role of the Son (who becomes Edward III), beautifully delivered by Samuel Boden." (The Guardian ★★★★)